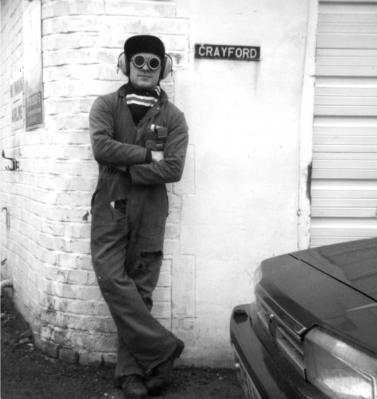

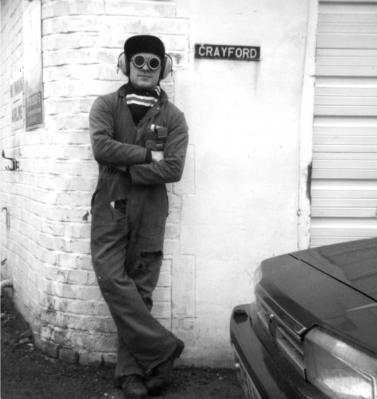

Alan Macro started working for Crayford at the age of eighteen. “When I first left school I hadn’t a clue what to do but the Careers people interviewed me and said ‘we’ve got a job for you, working in a technical drawing office where you’ll be doing all the prints for the draughtsmen.’ What it really meant was that I was making the tea and working as a general dogsbody for a company called Reliant Technical Services in Dunton Green. They did a lot of drawing work for building companies in the Middle East. I stuck it for about a year, but for me, the job was going nowhere, as I’m the hands-on type. I met this bloke called Gerrard Lawless in the Grasshopper one night and he worked for Crayfords. Over a pint he told me that they were looking for an apprentice-engineer to join them, but I had lined-up seven job interviews as an electrician. In the end they all went out of the window though, so I wound out working at Crayfords from about 1978 or ’79. I was a young lad and the only experience I had was what I’d been taught in Metalwork at School, but they taught me how to gas-weld, metal-folding, metal-cutting and everything else the job needed.” “I’ve come away from that with no qualification as they didn’t run a formal apprenticeship scheme, but what I experienced there has put me in good stead for everything else I’ve done since then. The workshop was a very long shed that ran back behind the cottage. The back end of the shop was on another level due to the rise of the ground and there was a ramp leading up to it. I remember one particular occasion we had a Mercedes 800 series that a guy from California wanted turned into a semi-convertible. It was a stretched low shape and as I drove it up the ramp there was a crunch and I was rocking on the fulcrum of the ramp - it had grounded in the middle where the gradient changed. We had to jack it up and push it onto the higher level. After we’d done the work we had to reverse the process to get it back down again.” I asked Alan what the conversion process was in general terms; how did they go about cutting the roof off a two-door car to make it a convertible with a soft-top. “…It’s actually a fairly crude process in some ways - take a Mark 4 Cortina as an example. In that higher section of the workshop there would be three or four cars we were working on in various stages of completion. You literally take all the wheels off and jack up a substantial timber running from side to side under the cills below the ‘b-posts’ of the doors. The jacks would just take the weight of the car, no more. You’d run across the roof from one b-post to the other with an air-saw and the roof would literally open-up with a gap of about half to three-quarters of an inch. At the back of the front wheel arch we’d cut out a rectangular hole and feed a heavy-gauge box-section tube of about two by four inches all the way through along inside the cill and cut the same hole in the rear wheel arch until the box-section was poking out into both wheel arches. We’d weld it into place and do the same on the other side. Then we’d lower the jacks holding our breath and hope the two pieces of roof section would pinch back together again, meaning that we’d got it right and the shell was self-supporting. That was all there was to it in most cases…” - he smiles. “Being honest, when you used to drive these things you could feel them ‘twitching’ - the body would flex and that was part of the character of the car. I spent about three years working on the cars before I got more involved with the ArgoCat side. It was two companies really, there was Crayford Auto Developments which was the car side, and Crayford Special Equipment which was the off-road vehicle side. It wasn’t two companies officially and we all worked both sides of the fence, but I predominantly worked on the ArgoCat side from then-on.

Alan Macro "...there were some really skilled guys working there - Richard Wood from Brasted was a top-dollar sheet metal worker, and Tony Channings, from the Tonbridge area, was a genius. He’d designed the first Aerospace ‘Mini’, prior to Crayford, with sub-frame chassis and a monocoque body-shell. The workshop foreman was a guy called Alan Dawkins, who was great and there was also a little guy called Tony England who was very knowledgeable. The chap I worked with on the ArgoCats was a very clever mechanic called Bob Hill and he taught me loads. He was from Biggin Hill and he was a nice bloke but could be a bit rough and ready. I was always asking him questions because I wanted to get on, and one day he picked up a pair of tinsnips and smacked them against a piece of sheet-metal on the bench - ‘stop keep asking me all those bloody questions’ he said. ‘Alright Bob, eat your sandwiches mate’ I said as I melted into the background - I realised I’d just annoyed him really, but there we go… I remember Grace ‘Biddie’ Norgate used to come in every day to clean the offices and make the tea - she and her old man lived right at the end of Nursery site overlooking Crayfords and she could just walk through from their back-garden. She was a wonderful woman who never got on the wrong side of anyone. We shared the same yard as Caffyns and we were always fighting with the lads there - we’d have water-fights and all sorts, just a great big laugh. Behind Caffyns’ workshop was an above-ground air-raid shelter with a concrete roof. We used to use it for storage of tyres and bulky stuff for the Argos, and I remember one day there was a car standing in Caffyns yard which was not in the best of conditions. After they’d all gone home that night, I went out there with the fork-lift truck and stuck the car on the roof of the shelter. When they came in the next morning, they couldn’t work out how it had got there” - he laughs.

Alan Macro “...the ArgoCats would arrive on a forty-foot low-loader, in four rows of three on their sides with one on-top of the three and filled with spares and extra tyres and all sorts. Where they parked-up, I used to drive the fork-lift round the A25 at about two miles an hour. We’d store them on their sides in the workshop, all stacked up next to each other. This was before Health and Safety came in, and there would be cans of petrol and bottles of battery acid sitting around the shop and we’d all be walking around with a fag-on. My first encounter with the Argos was as a lad down at the railway station in the 1970s. The railway had gone then, of course, but there was a big yard so Crayfords used to unload them there. They used to leave a batch of about sixteen of them there for several days and overnights as well. Us local kids would think ‘hey, this is good, a great big adventure playground.’ They weren’t fuelled up so we couldn’t drive them, but we clambered all over them, and had a great time.

David McMullan "...we did a lot of development and got it reliable in the end and a new customer arrived in the shape of the British Army. They’d started operating ‘snatch-missions’ where Maggie Thatcher wanted someone taken out of somewhere and they needed an ATV to carry eight or ten commandos along with their radio-gear, ammunition, heavy-weapons and explosives which could be carried in a MiG Flogger aircraft capable of landing on a football pitch-sized patch of ground. We developed the Argo so that it could carry a heavy machine-gun on the back and modified it so that the empty shell cases couldn’t find their way into the transmission train and they went down so well with the military that they came back for more - could we adapt it to carry a ‘Swingfire’ anti-tank rocket-launcher? It was no bigger than a set of golf-clubs, so yes we could do that. It was low profile in travel-mode so could drive around and hide behind small farm buildings. In action, a guy could get out of the Argocat and elevate the missile and use his binoculars to ‘sight’ the Swingfire. That was also successful and we were well in with the military by this time. Then Kent County Council came to us to help the clear up with oil on the beaches and in shallow waters from tanker spillages. Their request was could the Argo go down onto these contaminated beaches and spray a breakdown detergent onto the oil. Jeff Smith saw that project through and that vehicle which we called ‘Invictacat’ sold very well around the coast of Britain to local authorities with similar contamination problems. In the end someone developed a specialist vehicle from scratch, but up until that time we had a monopoly with the Argo derivative.

The basic Argo was around five thousand pounds in the 1980s, but if you added all the extras such as a snow plough, snow tracks, a sump shield, a winch, canopy, windshield with wipers and other stuff, that price could double. I remember there was an Argo on Gruinard Island off the coast of Scotland, where they did the Anthrax testing for biological warfare. It came down to us for servicing and we were told it was thoroughly decontaminated, but when we took the floor pans out the bottom of the body shell was full of water. It has drain plugs that you can remove, but nobody had done that and there were fish swimming around in the water! The Argo had a ladder frame chassis of 3mm folded steel, and when you took them over rough terrain you could feel the body move about - the chassis was designed to do that. With six or eight wheels in an extreme situation where you had opposing wheels on either side being the only contact with terra-firma you could really feel it as the chassis would literally twist as it was designed to do. It was a similar feeling but on a smaller scale to what you’d feel in the converted car. For a major overhaul the whole plastic body would come off in two halves, giving you access to the chain-drive, sprockets, axles, engine and gearbox”. We did a lot of ‘field-maintenance’ - I’ve replaced engines and re-built gearboxes on mountain-sides and all-sorts, and I’m sure there were one or two instances when I couldn’t repair them but I can’t recall any actual occasions so there can’t have been that many.

Alan Macro "... I became their chief test-driver and trouble-shooter and traveled all over the world for Crayfords. There were a couple of occasions when I nearly killed the lot of us, on one occasion I was in Wales with Eugene demonstrating the Argo to the Welsh Water-board Authority. All these ‘suits’ had climbed in the vehicle and Eugene said ‘take them down there Alan’ pointing to the forty-five degree slope of the bank of a reservoir. The more people you have on board the centre of gravity gets higher, so I set-off down this slope, but it suddenly dropped to nothing, a sheer drop. I thought ‘I’d better turn it round’ which wasn’t the best solution - I should have backed it up the bank, which it would easily have done. My instinct, however, on seeing the drop was just to steer away from it, and as I turned, the whole of one side of wheels left the ground and went up in the air. I didn’t feel it too much but Eugene told me afterwards they were well-high and he thought it was going to go over. As I completed the turn they came down onto the ground and there was more than enough power to head back up the hill. When I got back up the top I was greeted by a four-letter expletive - ‘that was a bit close wasn’t it?’ I asked, but the guys on board were all saying ‘that was good wasn’t it?’ - the vehicle had a hood on it so they hadn’t seen the reality of what happened. I thought about it later and realised we could have all gone over the edge…”

David McMullan “…We came down with just four of us – Jeff Smith, myself and two full-time members of staff, but we quickly built up our workforce with local people, almost entirely by word of mouth. If you needed a welder, you wouldn’t train one from scratch, the lads would put the word out around the local pubs and you’d put an ad in the local paper. Most of the welders who would respond would be interested in cars and to be given the chance to work on a brand new Ford Cortina convertible, they loved that. We had a fabulous morale in our workforce due to the fact that we were working on interesting things, and there would be a motor show once a year where they could see their work on display – they’d kit themselves up and be there on the stand and have a great time. Having said that we did train some lads from scratch, seventeen or eighteen year olds would be with us and be really useful by the time they were twenty-two, but we never offered a formal apprenticeship. There was a degree of paperwork involved, and we should have done, but to leave Crayfords with a glowing reference was a great apprenticeship in itself for a young man departing to move across the country to get married, or for family reasons. I always made sure they left with a letter that would have got them through the gates of heaven, but it was not a formal binding contract…”

I asked David if he would approach a dealership to prototype a new conversion, or would the dealership approach Crayfords.

“…very rarely would a dealership approach us from anywhere in Britain asking whether we would consider a particular project, but it did happen occasionally and we wouldn’t necessarily take it up. Somebody asked us if we would build a Jaguar convertible but my business partner hated Jaguars and thought they were the worst-built cars in Britain at the time. They weren’t the best-build in those days yet we nearly did take it on, but they were such a disaster in sales overseas, and I’ve always had this 3M rule in business – if it won’t sell in Montreal, Mombasa and Melbourne, well, don’t touch it. At that time they weren’t selling well in Coventry, let alone Mombasa and thank god it’s a different story now…” – he laughs.

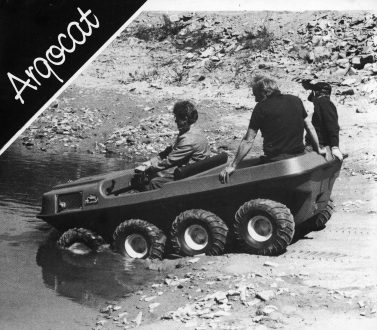

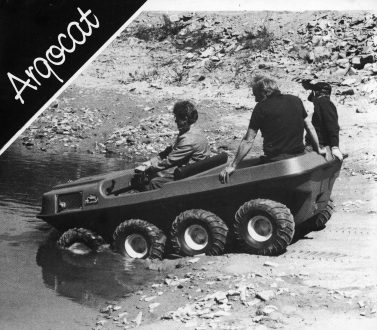

I ask about the Argocat venture that I remember back in 1986.

“… the Argocat helped us stay alive at the time. We saw this little amphibious vehicle – a tiny thing on six big balloon tyres at a motor show in Spain. It was made in Canada by a firm call Bwhoo. We bought a few in and they were badly built beyond belief and the big problem with these little cross-country vehicles was that they were using ‘Lucas’ British-made electrics which were awful. When the snow fell in Canada and everything got wet and sodden, these little vehicles with automatic transmission would just start-up and head-off on their own out of a car-park or wherever they were. One drove straight through the window of a big motor showroom in Toronto and created havoc, all because of Lucas electrics which weren’t designed to cope with exposure and wet conditions. We bought a few and worked on them and sold them, then I went over to Canada to visit the Argo Company as they were called. The lovely thing was, and still is, that the firm themselves were German and the engineering was top-notch. I got the franchise for Europe, and the deal was that they would send over the bits and we would assemble them in the UK in one form or another. Jeff sorted out some of the engineering design problems and in the end we sold them all over Europe.

We were naturals for the ATV (All Terrain Vehicle) market because Jeff Smith and I were both keen and experienced motorcyclists and both of us had lots of off-road experience. He had ridden in Scrambles and I had ridden in Trials, so we were both used to going uphill through thick mud in pouring rain and getting over tree stumps on the way.

Selling the Argocat we would go to hillside farms in Northumberland or wherever to demonstrate one and looking round the farm we’d say ‘if you can follow me in your Range Rover for twenty minutes wherever I go, i’ll give it to you.’

They were about eight thousand quid then, so everybody would take us up on the challenge. We sold a lot in Scotland, we had a main dealer up there called Aird Motors who were very successful. The weak point was the gearbox design and we had a very good mechanic working in Inverness, so I said to his boss ‘give him a week off, I want to send him to Canada to sort this gearbox problem out.’ He was sent to the factory and helped them get to the bottom of the problem with the input shafts. It was important because if an Argocat breaks down you have to send a mechanic up after it on another Argocat with all the spares and he has to repair it then and there – you can’t send a Range Rover after it, it wouldn’t be able to get near it.

We thought we were invincible and we would last forever, but we got it wrong because the computer age had arrived and computers were being utilised in many ways on production lines. When we had started out a production line produced a single car in droves, but a time came in the late 1980s when you could produce half a dozen of a different design in the middle of a long run because the computer had been programmed to do that. A time had arrived when big manufacturers could easily build two estate cars in a production line producing saloons and this, in part, was our downfall as builders of small-volume specialist cars to order.

But it was diversity that kept us afloat. Jeff and I always liked to travel, and we came back with some interesting ideas that had nothing to do with cars…”

Comments about this page

I have a few orginal Crayford argos. Did you guys ever build your own argocat? As on one model I can not find the argo label only the labels from Westerham.

Hi John, nice to hear from you! I interviewed David McMullen who owned Crayfords and to the best of my knowledge, they never built an Argo from scratch, though some of them were rebuilt almost from the bare shell. He said the original build quality was pretty poor and the resale contracts were from quite influential clients (Scottish estate owners, M.O.D. etc) so for their own credibility, Crayfords couldn’t take the risk of selling-on shoddy engineering as Argo had become a significant part of the business. Hope that helps, kind regards, Bill Curtis

I worked for Crawford Autos in the office. I remember one snowy day I went with Jeff and the argocat onto Limpsfield Chart. Someone filmed us as we drove around, to show how it handled in the snow. Very exciting!

Add a comment about this page